You know when you have a sweater with a thread hanging loose and you pull on it? And you keep getting more and more thread until your former sweater is nothing but a pile of sheep fur on the floor?

I decided it was time to get the air conditioning charged again and see if I could make the Imperial even cooler than it already is. Something about a black car and the hottest July on record.

First order of business: flush out the AC evaporator, condenser, and hoses with AC flush. This went fairly smoothly and flushed out less crud than expected. OK, that’s a good sign! Call the garage and schedule the re-charge.

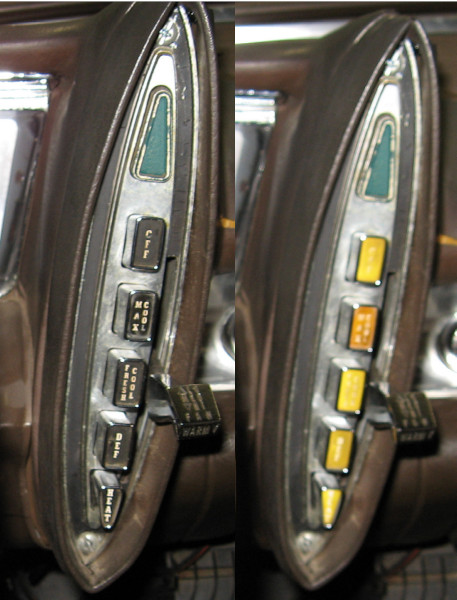

One of the idiosyncrasies of the new generic heater control is that it engages the AC compressor clutch when selecting MaxCool, Cool, or Heat. The temporary expedient was to unplug the compressor clutch over the winter. So I needed to plug the compressor clutch back in. And check to make sure it still worked. As you probably guessed, nothing.

Well, dogbreath!

First question: is it the clutch or the wiring? Hook up a temporary jumper to the clutch, connect it to the battery, and be rewarded with a solid clunk of clutch engagement. OK, wiring it is.

Next, check the fuses and make sure that power is going to the heater control. Yup, power is good at the fusebox. Sigh… Nothing left but one of my most dreaded jobs – remove the heater control!

Remove the glove box. Remove the ash tray. Remove the right hand defroster vent and hose. Remove the radio. Now start blindly reaching into the back of the dashboard to unbolt and remove the heater control. Yup, buried just as deeply as it used to be. Yup, just as awkward to get to as it used to be. Yup, just as many sharp edges in there as there used to be. Yup, I still have trouble finding things by braille.

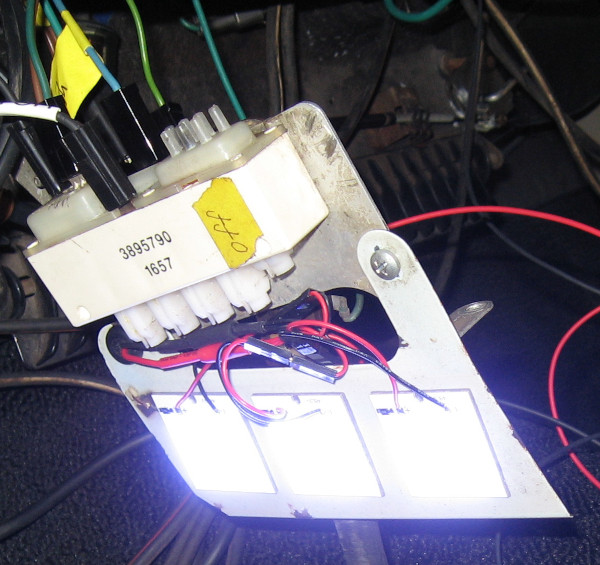

With the heater control finally out, wipe the blood off and start electrical trouble shooting. Hmm, no power to the clutch circuit. There was a similar problem last time. Fine, be that way! I have plenty of spare power circuits in the new fuse box, so just run a new dedicated power line directly from the fuse box to the heater control.

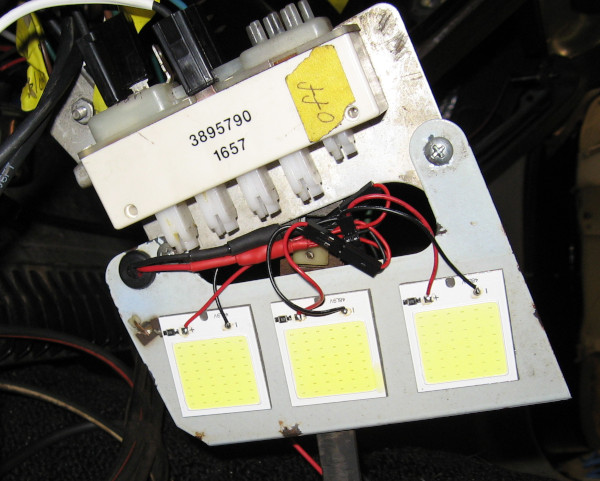

Try the compressor clutch again. This time I’m rewarded with a solid clunk when I push the button. Out of paranoia check the fan (which is the other part of the heater control): low, medium, and high, check. And the new LED lighting panels work (separate post on that). Reinstall the heater control. Check that everything is working. Still good!

You know, I should probably check the power antenna switch while the radio is out since the radio completely blocks access to this switch. Hmm, only goes down… OK, dig out the factory service manual and check the wiring. Three wires: power, up, and down. Of course the wires are different colors on both sides of the connectors…

Grab the multimeter and check all three wires. OK, this wire has 12V on it, so it goes to the center of the switch. The other two wires go to the other two connectors. And the antenna now goes up as well as down!

Reinstall the radio. Wrestle with the defrost vent and hose until they cooperate. Reinstall the ash tray and glove compartment and then sit back and admire a difficult job completed. Just to be sure, check out the compressor clutch and the fan. Satisfying clunk from the compressor, and fan works on low, medium, and… No high speed on the fan.

Well, carp! I can’t leave it like that.

Pull everything apart and start checking with the heater control now hanging under the dash. Everything works… OK, maybe a loose connector? Re-seat all connectors, re-install the heater control, wipe off the blood, and check. Everything works.

Re-install the radio. Check everything again before going any further. No high speed on the fan.

Pull the radio out. Check the fan. Works on Low, Medium and Hi.

What the freaking Hades is going on here?!? There is NO connection between the radio and the heater control. There is no way for the radio to interact with the heater or fan. This physically cannot be happening!

Pull everything apart. With the heater control hanging under the dash test all functions. Yup, with the radio removed the fan works on Hi.

As an alternative to an exorcism of the car I dragged out the wiring diagrams and multimeter and started tracing and checking each part of the heater circuit from the fusebox all the way to the fan.

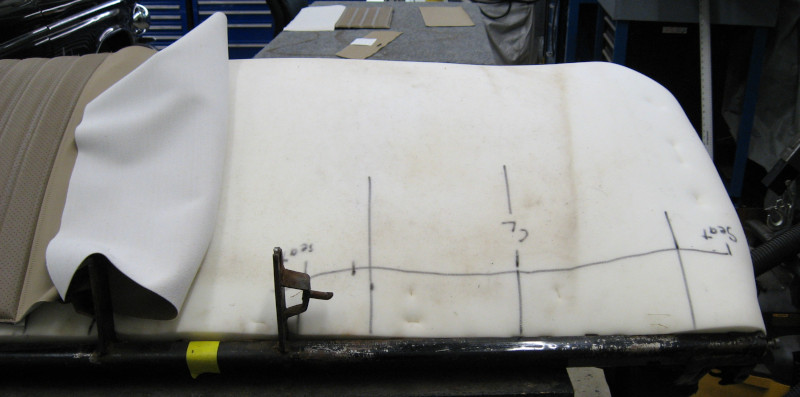

Hmmm, this is odd.. This connector near the fan feels like it has a broken wire. This is a butt connector covered with heat shrink tubing that should be one of the most solid and reliable parts of the entire circuit. And, of course, it is on the high speed circuit. This part of the wiring harness goes from the heater control, under the radio, and to the fan. Where it would be moved and jostled when installing the radio. No, no – this is just circumstantial evidence – don’t jump to conclusions!

The usual test is to tug on a wire and see if it comes out of the connector. This doesn’t work when marine grade heat shrink tubing glues everything together. The situation is suspicious enough that it makes sense to just cut the connector out and replace it.

With the old connector cut out might as well take it over to the workbench and slice off the heat shrink tubing to check the wire. Yup, damaged wire and a bad crimp. Moving the wire would make and break the connection. This evidence is more than just a smoking gun – it is like having surveillance video of the crime scene! The worst part is that these wires are new – I made them as part of installing the new heater motor. Yup, the usual idiot is to blame.

Double check and triple check the crimps when installing the new connectors. Make absolutely sure they are solid this time.

As part of the detailed trouble shooting I reviewed the heater control switches. I had wired the new switch just like the original factory switch, which meant (with this new universal switch) that the AC was running when heat was selected. Connect it differently and AC only came on for Cool and MaxCool, so I went ahead and hooked it up that way.

Check all functions — all good. Re-install the heater control. Check all functions — all good. Re-install the radio. Check all functions — all good. Re-install the defrost hose and vent. Check all functions — all good. Re-install the ash tray and glove compartment. Check all functions. Wait for it, wait for it…

All good! Not there yet – fire the car up and take it for a test drive. Check all functions — all good.

OK, I’m getting cautiously optimistic.

The AC recharge is now scheduled for next week.